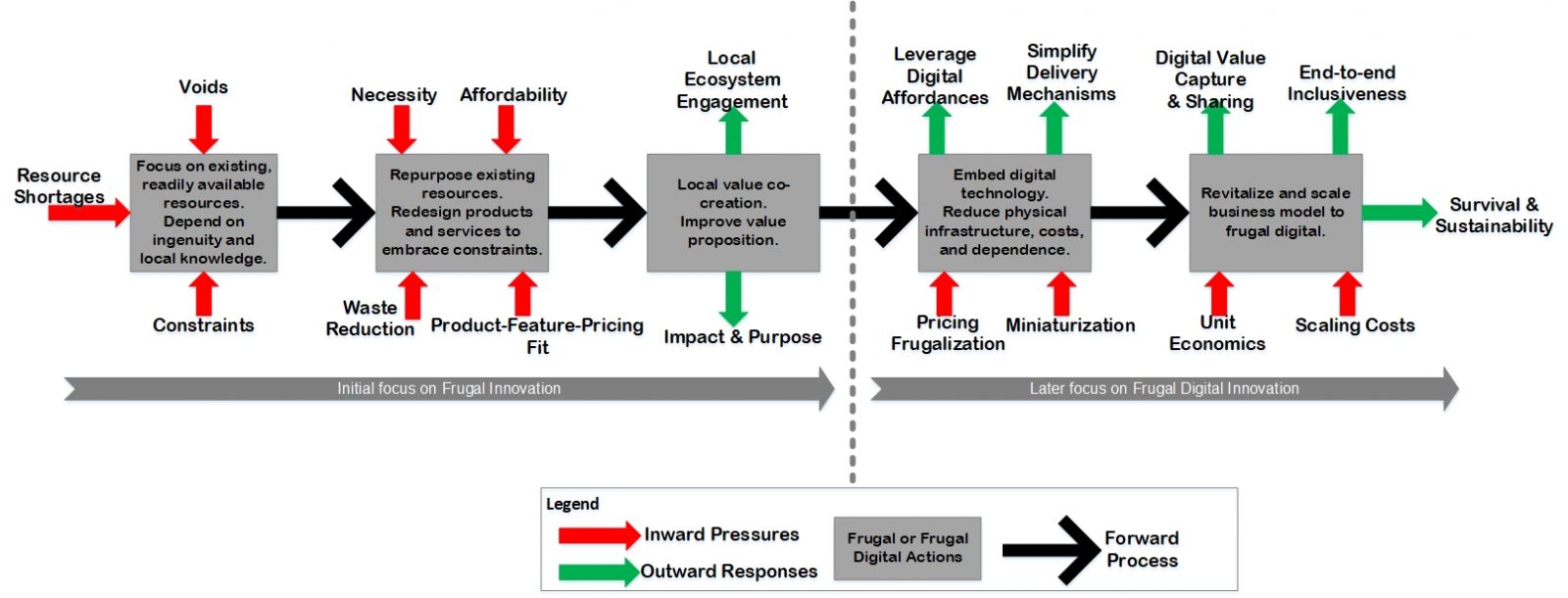

Although the pandemic has inevitably worsened the already resource-constrained conditions in which governments, health systems, for-profit and non-for-profit organizations, and individuals operate, there are signs of a resurgence of innovation, with a focus on reducing waste, repurposing existing resources, and localizing impact by leveraging digital technologies and Maker Movements. Suchit Ahuja and Stephanie Cadeddu discuss developments in Frugal Innovation.

With the subsequent systemic and global consequences of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the inability to escape constraining contexts, such as shrinking budgets, resource availability, workforce well-being, disrupted medical supplies, and ongoing economic uncertainties, suggests several important lessons that need to be assimilated: the ability to adapt quickly, embrace constraints by making the most of existing resources, and work innovatively to simplify problems.

These lessons resemble the paradigm of frugal innovation, which originated in the global South, primarily in India and some African countries. In these settings, resource constraints, socio-economic problems, and institutional voids are prevalent and require ingenious, out-of-the-box, and sometimes counter-intuitive solutions (Tiwari & Herstatt, 2019; Ahuja and Chan, 2019).

Frugal innovation rooted in ingenuity and necessity

In reality, frugal innovations have numerous attributes that are suitable for responding adequately to the current, turbulent global context as they are inherently rooted in affordability, simplification, sustainability, equitable technological and financial access, and efficient reuse or repurposing of resources through local scalability (Ahuja & Chan, 2016; Bhatti et al. 2020; Radjou 2020). Such innovations integrate the core needs of those targeted, often embedding inclusiveness into their processes, and are customized and adaptable to the context of use.

Doing better with less

From the perspective of economic and societal revival, frugal innovation serves as a new paradigm of thinking, processing, and development of products or services, embedding the core mantra of doing more with less for more people (Radjou & Prabhu 2015). In other words, its intrinsic value is not about depriving products and services of quality, rather simplifying their core functionalities by optimizing their essential performance (Weyrauch & Herstatt 2017). Composed of these multiple characteristics, frugal innovation is perceived to be in alignment with many of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) while SDGs also serve as enablers of frugal ideas (Cadeddu et al. 2019; Rosca et al. 2018).

Under-valued potential (so far!)

Although frugal innovation offers an opportunity for adaptation to any resource-constrained context, early scholarly research on frugal innovation tended to focus mainly on its “low cost” attributes and relegated it as a synonym for bottom-of-the-pyramid (BOP) solutions (Prahalad 2009). This perspective has weakened its potential usage as an impact-focused, value-creation mechanism by researchers, practitioners, funding agencies, and policymakers in advanced economies (Ahuja & Chan, 2019; Tiwari & Herstatt, 2019).

New evidence is changing perceptions

There is an impressive and growing body of research showing how frugal innovation could prove to be beneficial not just in the global South but also in advanced economies of Europe and North America (Directorate-General for Research and Innovation of the European Commission) et al., 2017; Knorringa & Bhaduri 2018; Sethi 2020).

The importance of frugal innovation in advanced economies can be attributed to many socio-economic events and changes that have taken shape in the past decade.

To begin with, the great recession of 2008-2009 caused upheaval in the financial markets and lowered disposable incomes for a large section of society (D’Andrea Tyson & Madgavkar 2016). Due to large scale layoffs, levels of income and spending suffered, while products and services evolved to become more sophisticated and prices for housing, healthcare, and college kept creeping up (Schoen 2016).

The consumption levels, although lowered temporarily, were still under question as global organizations such as the UN, World Economic Forum, and International Monetary Forum called for more responsible and sustainable consumption and spending by nations and society. Despite these calls, several innovations that are resource-intensive, unaffordable, and inaccessible for large sections of society and the world are observed. For example, a $600 automated juicer produced by a Silicon Valley startup was launched with much hype but failed to gain popularity due to its narrow niche, high price, and poor value proposition (Reilly 2018).

In parallel, the UN launched its 17 SDGs calling for renewed attention to address global challenges such as empowering vulnerable people, securing food access, providing equitable and quality education and health, reducing income inequality, and protecting the biodiversity (UN 2015). More recently however, the COVID-19 pandemic may have had reversing effects on the advancement of some SDGs (Benesty et al. 2021). The creation of the UNDP accelerator lab, which fosters frugal innovation through empowering grassroot capabilities in various developing and emerging countries, is one of the timely initiatives to achieve the SDGs promptly (Gustilo Ong & Gustale 2020) and potentially address the pandemic side-effects.

The Covid-19 pandemic has indeed brought the global economy to its knees and imposed unforeseen constraints on how business, public health? governance, policy, and societal transactions are conducted (Radjou 2020). Nonetheless, the pandemic has provided impetus to several sections of society to adapt and ‘frugalize’ their lifestyle as their access to previously available resources has been substantially reduced (Herstatt & Tiwari 2020).

Mainstreaming Frugal Innovation

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced advanced economies to look for frugal innovation solutions to overcome complex constraints and voids. Some of the reasons might be that the COVID-19 pandemic may have highlighted the fabric of a “dysfunctional capitalist economy” within which innovators working on traditional sustainable development and corporate social responsibilities might not be sufficient (Radjou 2020). This pandemic has brought to light practices that challenge conventional innovation norms, which seem to be inspired by frugal innovation, and are in high demand (Cadeddu, Ahuja & Alami 2020; Ramalingam & Prabhu 2020).

Moreover, new research is focusing on improving the robustness and reliability of frugal innovation in advanced economies (e.g., Skopec et al. 2020), thereby addressing a key criticism about its lack of evidence-based evaluations (Harris et al. 2020). This is timely with respect to the pandemic-induced constraints, as there has been an exponential rise of appropriation of the frugal innovation concept. Examples are numerous, such as for point-of-care diagnosis for outbreaks (Miesler et al. 2020), in the assistive technology sector including prosthetics (Directorate-General for Research and Innovation of the European Commission et al., 2017) or in the organization of health care delivery in the USA health systems (Bhatti et al. 2017b). As a result, frugal innovation is receiving much more attention from academia, industry, policymakers, and government.

Frugal innovation seems to be driven during the pandemic by several stakeholders belonging to diverse sectors of the economy.

Exploring COVID-19 responses, Bhatti et al. (2020) showcase a number of innovations stemming from governments, non-for-profit and for profits enterprises, and citizens whereas the literature has regularly explored the concept of frugal innovation from the private sector perspective. The role of governments has been understated, in particular during a crisis of this magnitude and scope. Despite a number of calls inviting governments to consider frugal innovation in the last decade (e.g., Nowlan 2016; Gilman & Gover 2016), governments are only now starting to pay attention to social and frugal innovation (e.g., German government) (Gegenhuber 2020; OECD 2020). For example, Sarkar (2020) suggests “government frugal innovation” based on the Indian Kerala government’s COVID-19 responses where the government acted as a developer and a facilitator of “low-cost, and efficacious technological solutions” in partnerships with a multitude of stakeholders (Sarkar 2020, p.8).

Opening doors for novel innovation practices

The COVID-19 pandemic has unintentionally opened doors, and created a momentum, for novel innovation practices that are necessary in such dynamically-shifting contexts but did not receive mainstream attention in the past.

These ‘pandemic’ innovations are often based on open-source knowledge, inclusivity, grassroot-driven initiatives, 3D printed products and digitized processes as well as decentralized care services (Bhatti et al. 2020; Cadeddu, Ahuja & Alami 2020).

In light of these practices, frugal innovations that have emerged during the crisis accentuate an array of distinctive characteristics. According to Bhatti et al. (2020), there are four underpinning characteristics of these frugal innovations.

Characteristics of frugal innovation

– reuse

– repurpose

– recombination of resources

– rapid solutions

These characteristics contrast with, and expose, traditional mindsets that tend to nurture individualist and resource-intensive practices. These tend to prioritize short-term financial and economic growth objectives, inflexible, non-localized, non-customized supply chains and lack of accountability processes for social and environmental issues (Agence France-Presse 2020; Radjou 2020).

Another common attribute underpinning many frugal innovations that has emerged during the current pandemic is its preeminent digitalized nature (e.g., Bhatti et al. 2020; Sarkar 2020).

With the rise of frugal products and services that leverage digital technologies like big data, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, blockchain and m-health, among others, digitalization is now an imperative within the frugal innovation domain. Examples of this are found in India with an affordable, non-invasive, privacy-controlled AI-enabled breast cancer detection (niramai.com) and the IoT-enabled screening of remote, rural patients by top city doctors in India (karmahealthcare.in). These were developed harnessing local resource constraints conditions; they could not rely on the current systems and infrastructures, which shaped these innovators’ responses to reach rural or remote areas.

Digitalization of Frugal Innovation

Information and communication technologies have been on the rise over the last two decades, greatly influencing the digitalization of conventional processes, products and services into virtual ones (Novintan et al. 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous digital innovations have proliferated and overcome conventional institutional barriers. For example, telehealth has rapidly replaced physical consultation and allowed to reach Quebec communities (Arsenault et al. 2020) even though this digital innovation has faced ongoing obstacles at regulatory, financial and organizational levels over the last few years (Alami et al. 2018).

Recent frugal innovation practices are also enabled by the digitalization of processes, products or services, leveraging existing asset-light SMACIT (Social Media, Mobile, Analytics, Cloud, and IoT) technologies as well as new technologies such as AI, 3D printing, blockchain, etc.

For example, Raspberry Pi is a computing device which consists of a single board and costs around $35. It is the epitome of “frugal” and “miniature” product mindset required for frugal innovation and has seen applications ranging from teaching programming to high school students to deployment of robotics and scalable cloud networking equipment (Dagit 2017). These technologies may seem expensive and difficult to acquire for firms working on a frugal innovation strategy.

However, it is not the technologies themselves that allow them to be affordable to startups and small firms with limited resources, it is rather the unit economics-based, subscription business models (Ahuja and Chan, 2019; Agarwal et. al, 2019). This, in turn, drives frugal digital products and services. For instance, in the past it would cost millions of dollars for a startup to develop its own big data-based technology infrastructure, yet now it can simply purchase a monthly subscription for IBM or Amazon AWS modules for a fraction of the cost.

In another striking example of frugal digital innovation, EzeRx, a startup in India, has developed a device that can non-invasively detect anemia and other liver and lung diseases and has designed an affordable business model that provides this service at 35 Rupees (approx. USD 0.50) per test to patients (https://ezerx.in/products/).

Undoubtedly, negative impacts and externalities still exist when digital innovation is exploited unreasonably (e.g., rebound effects, resource-hungry and heavy materials infrastructures, inequal access and reach to digital novelties and data privacy issues) (Le bas 2020; Rieger 2021; Van Dijk 2017).

Nonetheless, there are examples of open data initiatives in South America and Taiwan where sharing health information with the government to design frugal-digital solutions was deemed necessary to curtail the negative consequences to public health and safety (https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-04-22/taiwan-offers-the-best-model-for-coronavirus-data-tracking).

Interestingly, the intersection between the realms of digitalization and frugal innovation can offer affordable, accessible, rapidly scalable, and high-impact solutions, particularly in resource-constrained settings and across a variety of sectors (Ahuja & Chan 2019; Howell et al. 2018). Such frugal digital innovations do not imply that new machines that transmit or treat information (e.g., medical products, servers, tablets) will flourish considerably.

Frugal digital innovations rather seek to replace the multitude of inefficient, complex and pervasive digital innovations (e.g., digital tools, technologies, platforms, value chains, and business models) (Howell et al. 2018) grounded in previous traditional mindsets; and instead, serve better and more underserved parts of the population. Frugal digital products and services utilize the underlying affordances of digital technologies, platforms, and infrastructures (Nambisan et al., 2019) to innovate in resource-constrained contexts enabling value co-creation and distribution. Frugal digital innovation often takes shape in ecosystems that involve physical, digital, and social actors and transactions (Agarwal & Brem 2021; Ahuja, in press).

Rise of the Maker Movement

Frugal digital innovations offer many incentives including for the development of decentralized, circular, low-tech and sharing models of innovation processes and infrastructures.

For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the emergence of “low-tech labs” and “Makers” (Corsini et al. 2020), which embraces intrinsic values such as usefulness, accessibility and sustainability.

The aim of the low-tech movement is to sober societies’ lifestyles, consumption and production and to build more respectful and resilient societies (lowtechlabs.org). Low-tech labs focus on digital fabrication of tools and exemplify that “frugality is driven by the ability of makers to locally replicate, adapt and produce these innovations – according to their own needs and constraints” (Corsini et al. 2020, p.11). This mindset has even been leveraged by large private organizations, that are collaborating to share their capabilities through a Maker Movement approach. Examples of this include: 1) the SEBlab (Makertour n.d.) and 2) Decathlon choosing to adapt its scuba diving equipment into COVID-19 face masks (CNRS info 2020).

Is the future frugal?

The COVID-19 pandemic has also provided an opportunity to communities to build resilience through frugal digital technologies. In line with the principles of frugality and digitalization, communities leverage “readily-available digital technologies” to address the constraints imposed by the pandemic in a timely and self-reliant manner (Sadreddin et al. 2020). In light of the UNDP accelerator lab’s enthusiasm for fostering grassroots innovation capabilities through frugal innovation (Gustilo Ong & Gustale 2020), potentially transformational changes can arise from combining both frugal and digital realms at community level. To emerge from the current pandemic and to rejuvenate a post-pandemic world, we may need to rethink the role of resilient communities in innovation practices, empower them with frugal digital solutions, and encourage them to embrace constraints, become adaptable, and focus on repurposing resources that are readily available.

Additional resources

How does frugal innovation offer a new form of solidarity in a pandemic and post-pandemic context?, by Stéphanie Bernadette Mafalda Cadeddu, Suchit Ahuja et Hassane Alami. (PDF)

Agarwal, N., & Brem, A. (Eds.). (2021). Frugal Innovation and Its Implementation: Leveraging Constraints to Drive Innovations on a Global Scale. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67119-8

Agence France-Presse (2020) Vers des pandémies plus fréquentes et plus meurtrières. Radio-Canada. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1745345/pandemies-frequence-onu

Ahuja, S. (in press). Frugal Digital Innovation: Leveraging the Scale and Capabilities of Platform Ecosystems. In Agarwal, N., & Brem, A. (Eds.). (2021). Frugal Innovation and Its Implementation: Leveraging Constraints to Drive Innovations on a Global Scale. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67119-8

Alami, H., et al., (2018) The challenges of a complex and innovative telehealth project: a qualitative evaluation of the eastern Quebec Telepathology network. International journal of health policy and management. 7(5), p. 421.

Arsenault, M., et al., (2020) Covid-19–Exercer la télémédecine durant la pandémie. Canadian Family Physician https://www.cfp.ca/news/2020/03/26/3-26-2..

Bhatti, Y., Prabhu, J. & Harris, M. (2020) Frugal Innovation for Today’s and Tomorrow’s Crises. SSIR. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/frugal_innovation_for_todays_and_tomorrows_crises

Bhatti, Y., Prime, M., Harris, M., Wadge, H., McQueen, J., Patel, H., Carter, A., Parston, G., & Darzi, A. (2017a). The search for the Holy Grail—Frugal innovation in healthcare from developing countries for reverse innovation to developed countries. BMJ Innovations, 3, 212–220. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2016-000186

Bhatti, Y., Taylor, A., Harris, M., Wadge, H., Escobar, E., Prime, M., Patel, H., Carter, A. W., Parston, G., Darzi, A. W., & Udayakumar, K. (2017b). Global Lessons In Frugal Innovation To Improve Health Care Delivery In The United States. Health Affairs, 36(11), 1912–1919. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0480

Benesty et al. (2021) Reimagining Global Health After the Coronavirus. https://www.bcg.com/en-us/publications/2021/reimagining-global-health-post-pandemic

Cadeddu, S. B. M., Donovan, J. D., Topple, C., de Waal, G. A., & Masli, E. K. (2019). Frugal innovation and the new product development process: Insights from Indonesia. London: Routledge.

CNRS Info. (2020). En 17 jours un consortium adapte un masque de plongée pour lutter contre le coronavirus | CNRS. https://www.cnrs.fr/en/node/4691

Corsini, L., Dammicco, V., & Moultrie, J. (2020). Frugal innovation in a crisis: The digital fabrication maker response to COVID-19. R&D Management, . https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12446

D’Andrea Tyson & Madgavkar (2016) Inequality, stagnating incomes and the Great Recession: Are things getting better? https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/09/inequality-stagnating-incomes-and-the-great-recession-are-things-getting-better/

Dagit, R. (2017). Providing enterprise solutions with the Raspberry Pi. ByteLion. https://www.bytelion.com/providing-enterprise-solutions-with-the-raspberry-pi/

Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission), Fraunhofer ISI, & Nesta. (2017). Study on frugal innovation and reengineering of traditional techniques. [Website]. Publications Office of the European Union. http://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/20d6095a-2a44-11e7-ab65-01aa75ed71a1

Gegenhuber, T. (2020) Countering Coronavirus With Open Social Innovation. SSIR. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/countering_coronavirus_with_open_social_innovation#

Gilman, H.R. & Gover, J.A. (2016) Structuring Innovation in the Next Administration. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/structuring_innovation_in_the_next_administration#

Govindarajan, V. & Trimble, C. (2012) Reverse Innovation: Create Far from Home, Win Everywhere. Harvard Business Press.

Gustilo Ong, A. and Gustale, E. (2020) Frugal Innovations to Accelerate Sustainable Development. UNDP Accelerator Labs Global Team on Medium. https://acclabs.medium.com/frugal-innovations-to-accelerate-sustainable-development-18cacc6bd75f

Harris, M., Bhatti, Y., Buckley, J., & Sharma, D. (2020). Fast and frugal innovations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Medicine, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0889-1

Herstatt & Tiwari (2020) Opportunities of frugality in the post-Corona era https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/220088/1/1700692038.pdf

Howell, R., van Beers, C., & Doorn, N. (2018). Value capture and value creation: The role of information technology in business models for frugal innovations in Africa. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 131, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.09.030

Knorringa, P., & Bhaduri, S. (2018). Working Paper 6—Frugal Innovation in EU Research and Innovation Policy (p. 11). CFIA Working Paper Series.

Le Bas, C. (2020). Quand l’innovation se fait frugale. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/quand-linnovation-se-fait-frugale-127670

Makertour.fr (n.d.) SEBLab. https://www.makertour.fr/workshops/seblab#presentation

Miesler, T., Wimschneider, C., Brem, A., & Meinel, L. (2020). Frugal Innovation for Point-of-Care Diagnostics Controlling Outbreaks and Epidemics. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01712

Nambisan, S., Wright, M., & Feldman, M. (2019). The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Research Policy, 48(8), 103773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.03.018

Novintan, S., Mann, S., & Hazemi-Jebelli, Y. (2020). Simulations and Virtual Learning Supporting Clinical Education During the COVID 19 Pandemic [Letter]. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 11, 649–650.

Nowlan, O. (2016) Learning from frugal innovation: three lessons for local government https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/learning-from-frugal-innovation-three-lessons-for-local-government/

OECD 2020 OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19) Innovation, development and COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities and ways forward

Prahalad, C.K. (2009) The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits. 5th anniversary edn, FT Press.

Radjou 2020 The rising frugal economy. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-rising-frugal-economy/

Ramalingam, B., & Prabhu, J. (2020). OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19)—Innovation, development and COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities and ways forward. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/innovation-development-and-covid-19-challenges-opportunities-and-ways-forward-0c976158/

Reilly, C. (2018). Juicero is still the greatest example of Silicon Valley stupidity—CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/juicero-is-still-the-greatest-example-of-silicon-valley-stupidity/

Rosca et al. (2018). Does frugal innovation enable sustainable development? A systematic lit. review. The european journal of development research 30 (1), pp.136-157

Rieger, A. (2021). Does ICT result in dematerialization? The case of Europe, 2005-2017. Environmental Sociology, 7(1), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2020.1824289

Sarkar, S. (2021). Breaking the chain: Governmental frugal innovation in Kerala to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Government Information Quarterly, 38(1), 101549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101549

Sadreddin, A., Ahuja, S., & Chan, Y. E. (2020). Digital technologies will help build resilient communities after the coronavirus pandemic. The Conversation. Retrieved February 10, 2021, from http://theconversation.com/digital-technologies-will-help-build-resilient-communities-after-the-coronavirus-pandemic-144449

Schoen, C. S. (2016). The Affordable Care Act and the U.S. Economy: A Five-Year Perspective. Commonwealth Fund. https://doi.org/10.15868/socialsector.25101

Sethi, P. (2020). Resilient Cities, Post COVID-19: Accelerating Innovation | Future Cities Canada – Building Infrastructure to Handle Trauma. https://futurecitiescanada.ca/stories/resilient-cities-post-covid-19-accelerating-innovation/

Skopec, M., Grillo, A., Kureshi, A., Bhatti, Y., & Harris, M. (2020). Double standards in healthcare innovations: The case of mosquito net mesh for hernia repair. BMJ Innovations, bmjinnov-2020-000535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2020-000535

Van Dijk, J. (2017). CLOSING THE DIGITAL DIVIDE The Role of Digital Technologies on Social Development, Well-Being of All and the Approach of the Covid-19 Pandemic. (pp. 1607–1624). United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/07/Closing-the-Digital-Divide-by-Jan-A.G.M-van-Dijk-.pdf

Weyrauch, T. & Herstatt, C. (2017). What is frugal innovation? Three defining criteria Journal of Frugal Innovation, 2 (1), p. 1.