How can R&D teams within large, global, research-intensive organisations accelerate the process of radical, market-oriented, new product development in the fuzzy-front-end of the innovation process?

In this post Dr Peter Robbins, DCU Business School, writes about a fascinating organisational experiment, a ‘Radical Innovation Tournament’, which took place in the R&D division of a Top 3 Pharma corporation.

The Radical Innovation Tournament was an R&D-based, international innovation challenge that sought to get more ‘game-changing, radical ideas’ into the organisation’s new product development funnel.

Criteria for decisions at the front end of innovation?

Many researchers have identified the front end of innovation (FEI) as the most important phase of the innovation process. Ironically, despite its importance, it is the least studied phase. But managing FEI is challenging and confusing because the data on which decisions are normally based is either, at best, unclear or, more commonly, totally absent. This is particularly so when organizations are targeting radical innovations when complexity and uncertainty are highest.

With some colleagues, I’ve recently conducted an intensive study of the biggest and most ambitious organisational experiment ever published about a pharmaceutical company (Peter writes). Its aim was to help clarify how radical innovations might be achieved in global, multi-brand, R&D-intensive organizations.

Goal orientation is key

During the study, the area of motivation or goal orientation of the teams came to the fore as a key factor.

For background, Carol Dweck’s motivation research, in the 1980s, found two types of goal orientation: either learning goal orientation or performance goal orientation.

- Learning goal orientation – individuals with this orientation approach a task with the goal of learning for its own sake – and creating new knowledge.

- Performance goal orientation – these individuals attempt simply to gain favourable judgments: to look good in certain situations or avoid negative judgments from others – or being seen to lose. They choose tasks in which they are likely to look good and avoid ones where they might not look so good.

Radical Innovation Tournament

The company put together two R&D teams of about 12 PhD scientists to compete against one another in a Radical Innovation Tournament.

The two teams were as equivalent as possible and were tasked with generating radical innovations for the business. It was specified that the ideas should have potential for sales of €20m. The brief was as simple as that.

The teams were given nine months – they were given the name of a hotel in New York where they were to turn up and present their ideas to the Senior Leadership Team. A leader was named for each team and the leader was given a budget of £200k – for which they did not have to provide any spending rationale. Neither did they have to make any interim report or check in along the way.

In short, they were given carte-blanche and liberated from the conventional corporate reporting procedures.

One team was located in an R&D Centre of Excellence in New Jersey and the other in an equivalent R&D (CoE) Hub in the UK.

The leader of the UK team was a leading scientist with a high reputation: he had little people-management experience prior to this initiative. The leader of the US team was an experienced project manager who had managed teams before.

An organisational experiment to generate supplementary radical ideas for growth:

1. Two teams competing against each other (US vs UK)

2. 12 scientists on each team (almost all PhDs)

3. Initiative to run over nine months, concluding with a presentation in Manhattan

4. Both teams working to an identical brief

5. Both teams provided with a $200k budget

6. Both teams given unprecedented autonomy in managing their time and resources

7. Team members expected to devote 20% of their time to RIT

Figure 1: The rules of the game

What is radical innovation?

It’s probably worth exploring how the company elected to define ‘radical innovation’.

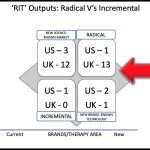

To qualify as a ‘radical innovation’ the ideas had to be both novel across two dimensions: they had to be novel therapy areas – ie markets or therapy areas in which the company did not yet have a footprint and they had to be aimed at a consumer group that was also new.

As the chart below indicates, it was the UK team which outperformed the US group and produced considerably more radical ideas. Their ideas revolved far more around new therapy areas and new patient or consumer groups.

Disruptive innovation vs incremental

The outcome was fascinating with one team (UK) clearly excelling at the creation of radical ideas while the US focused mainly on incremental innovation – building on established products and merely proposing minor line extensions.

Closer investigation revealed that at the heart of the difference was the approach of the leader of each team.

Our interviews showed some crucial differences between their philosophy and their motivation.

Figure 2: How the ideas were classified

US team wanted to look good – The US team set out to win: to look good and this translated into developing ideas in a way that would make them palatable to the company. They avoided proposing anything too risky as they believed that despite asking for ‘radical’ innovation, the company really would not support such radical ideas. Below are some direct verbatims from interviews with the US team:

“From the beginning I was looking at the end-point and what we would be presenting and so I set up a project planning tool and managed it like a project and I knew the other team were unlikely to be doing that, I invested in dedicated software so we could capture our ideas and nothing would be lost.” (TL)

“On this side of the pond I think we went into a bit more of how things could be executed. Whereas the UK team went into more of the pie in the sky really unique idea type stuff. People could see they weren’t really thought through like ours.” (TM)

“Although we were asked to come up with ideas or concepts that were totally radical and different from the areas we were operating in; blue sky ideas– I just didn’t do it. I didn’t think they would go with these ideas – I didn’t think they would back them so I didn’t support any radical, novel ideas in our team.”(TM)

UK wanted to be novel and creative – In the UK, the leader stayed faithful to the scientific credentials, heritage and skills of his team. He asked them to follow science – to have that as their north star and to make connections and establish networks in scientific groups. He did not set out to win the contest but to develop novel, creative, original ideas.

“We tried to provide people with the opportunity to learn about new areas, find out new information, speak to new people, from speak to new people, from which they could generate new thread.” (TL)

“I felt that we should at least stick with our scientific heritage, try and look at science in a different way, come up with novel technical solutions rather than trying to pretend that we were commercial folk when we weren’t.” (TL)

“We were inviting the external experts; we were highlighting to each other interesting sources of new scientific development and trying to create an environment where people would explore new areas and find out something they thought was of interest and then develop threads.” (TL)

Technology push or market pull?

We found evidence from across the UK team, including the team leader, of a preference for situations that are challenging and risky – consistent with a learning goal orientation. As one team member said: ‘for me, the whole beauty of this process was that we were free to go and explore’. The team had a passion to develop new knowledge and engaged with engaged with external parties in their quest to bring new knowledge into their innovations.

The team also adopted a flexible approach to learning – as one team member described it: ‘it was like a playground where you could do exactly what you wanted’. This learning orientation was shared by the team and remained stable throughout the 9-month duration of the project.

The US Team manifested a calculated, systematic intention to win the competition by second-guessing that senior management, despite their call for radical ideas, would really prefer to get ideas that were actionable in the short to medium term. They cynically, but correctly, assumed that the organisational appetite for breakthrough ideas, despite the corporate rhetoric, was low. Hence, they confined themselves to incremental ideas. They spent less time on the science and more on making sure that their business case was watertight.

On reflection, if you are leading a team in a tournament like this, you have essentially two choices. You can focus on the pure technical side of the science, stretching the team’s thinking about what might be – moving from point A to point B or, alternatively, you can move closer to the role of marketing; obsess about current consumer pain- points and focus on near time ideas which are closer to the market and for which market data is, therefore, more accessible – moving from point A to point A+.

In this case, the UK team chose to stick close to the science and not allow ‘first rate scientists become second rate marketers.’ This can also be characterised by the dichotomy of explore (UK) versus exploit (US): or of tech-push (UK) versus market-pull (US).

Who won?

Objective viewers were surprised that the US team were declared winners.

The senior vice president (and most senior member of the judging panel) explained the decision to declare US the winners was largely because they had presented ideas that the company could easily absorb into its pipeline, even though he also noted that ‘what the US did was put an awful lot of effort into making videos of consumers. What I wanted was some rigor and depth of work on the basic science.’

In short, the strategy of the US team paid off: they were more attuned to the company culture.

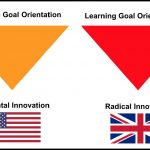

Figure 3: The connection between goal orientation and innovation ambition

Most of the other judges also were disappointed with the ambition of the US team’s ideas, considering them too near term, too incremental, and lacking any radical element. They also considered the UK team to have developed more genuinely novel, radical and creative ideas.

As one judge commented: ‘The UK team were wild, wacky and weren’t inhibited – but the US team, driven by that structured approach – it was all facts and data. It seemed very much driven by potential commercial opportunities. The UK team were prepared to go that little bit further. A lot of the US stuff had been done before and a lot of the UK stuff was completely off the wall, in a good way, new – just what we wanted.’

Culture determines outcome

In summary, the leadership of the innovation team can set the tone for the ambition of the team.

If they are imbued with a learning goal orientation, their ambition will be high and their work is more likely to deliver genuinely novel, original ideas. Conversely, if they have a performance goal orientation, where their real ambition is to make a good impression on senior management – then they are likely to be anchored in the incremental.

Part of this research is already published in R&D Management – if you’d like to read more, see: Robbins and O’Gorman, 2015.

Guest post from Dr Peter Robbins – DCU Business School. See his research on Google Scholar here.