In R&D management it is important to be aware of, and incorporate, external ideas and technologies into your new product, service, or process portfolio, writes Phil Kennedy.

He says: “Innovative companies do this as a matter of course as part of their innovation management systems (IMS). However, to do this effectively requires people in your organisation who not only have the domain knowledge to appreciate the relevance and potential value of the external idea or technology, but also have the capability and advocacy to “sell” it to internal stakeholders. This dual activity is essential to promote action and derive value for your company. As Helen Keller commented ‘ideas without action are useless’.”

Phil, a practitioner with a strong track-record in new product development and external knowledge acquisition at 3M, has reviewed the following paper for R&D Today.

How Individuals Engage in the Absorption of New External Knowledge: A Process Model of Absorptive Capacity

David Sjödin , Johan Frishammar, and Sara Thorgren

This paper studies the role of individual knowledge workers in engaging in knowledge absorption through the “absorptive capacity (AC) process”.

Absorptive Capacity is defined as “… ability to recognise the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends.”

To summarise, this paper has a number of key findings:

Individuals engage in the absorptive capacity (AC) process in three ways:

- Recognising the knowledge potential through evaluating the technological feasibility and assessing the motivation to assimilate the knowledge – this gives them the perceived value of the knowledge

- Validating the knowledge value through checking the legitimacy of the knowledge and by knowing the business value (implicit here is the knowledge worker having a good understanding of the company’s strategy)

- Championing the knowledge integration through lobbying for support and securing the resources to integrate and apply the knowledge within the company.

Observations

- These personal attributes parallel the company AC process of recognising the value of, assimilation of, and exploitation of, new knowledge.

- Individuals that are skilled at absorbing knowledge from the environment and assimilating it into the company are key to making their company innovative.

- The degree to which the knowledge (ideas) either get exploited, terminated or lost in limbo depends on the proficiency of the knowledge worker.

Elements for successful exploitation of AC

The paper provides a process perspective on AC from potential to realised AC. It provides insights into how individuals and companies can better manage knowledge absorption in practice, and how individuals can close the gap between potential and realised AC.

Important elements for success in the three stages of AC vis-a-vis the individual are:

Recognition:

- Innovative interest. The individual’s willingness and motivation to identify external knowledge – there needs to be “innovative interest” on the part of the individual. Those that excel are individuals with curiosity, a drive for problem‐solving and innovation, and an interest in technology.

- Bring benefit. Individuals need to feel that they will benefit from bringing new knowledge into the organisation, either materially or in terms of standing in the organisation

- Intrinsic motivation. Autonomy for the individual is strongly linked to intrinsic motivation of an individual

- Abilities. Individual abilities such as being oriented by learning goals and being innovative

- Evaluation. Experience of the individual which enables the evaluation of technical feasibility – it’s no good bringing in useless knowledge into the organisation and wasting internal time and resource.

- Tactics. A lack of experience may also be a barrier to getting one’s idea heard in the organisation. Here a less experienced individual may adopt an alternative strategy of working with a person of high [technical] status in the organisation.

Assimilation:

- Connection. The ability of the individual to connect the external knowledge to the broader organisation

- Communication. Being able to communicate in the language of others to ensure knowledge assimilation. Individuals need to able to engage in stimulating group acceptance by promoting new ideas, knowledge, or technology within groups, teams, or departments.

- Value. The demonstration of business value is key, so individuals need to be proficient in identifying business cases/needs.

- Gatekeeper. The individual acts in a gatekeeper role combining the external searching with internal assimilation efforts and creating a pool of accepted, validated external knowledge that the organisation can then draw upon for new ideas.

Exploitation:

- Lobbying. The individual’s ability to secure organisational commitment through effective lobbying for support and securing resources

- Tailoring. Effective individuals combine assimilation with utilisation – such individuals are referred to as “shepherds” and can contribute by tailoring the assimilation process to aid wider knowledge exploitation

- Politics. There is an element of influence and power in the AC process – individuals may need to compete for resources to exploit their new knowledge/idea. For success here, the individual will benefit from understanding the internal power structure and politics of the organisation.

- Engagement. One needs to know who to seek out and influence. Don’t just rely on putting the knowledge into some process like an idea management system. Get as many people on board before any formal idea assessment meeting.

- Bootlegging. Securing resources for exploitation is key but competition for resources can lead to even good external ideas not being pursued. Here the resourceful individual may go outside of official channels and resort to “bootlegging” to explore the idea further.

If you want to read the detail of this paper, I would advise that you focus on three things:

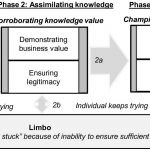

Figure 1, which gives a great summary of the themes and overall categories distilled from the research interviews with 37 individuals’ in‐depth, face‐to‐face interviews

Figure 2 and its associated phase descriptions in the text

Table 3 – the representative quotes from interviewees, which illustrate well, in non-scientific language, the source of the summary dimensions and themes that the paper crystallises.

(Open a section below to view each)

Data Structure

A Process Model of How Individuals Engage in the Absorption of New External Knowledge

Representative Supportive Data for Each Second‐Order Theme

Dimensions and Themes with Illustrative Quotes

Valuing knowledge potential

Motivation to assimilate

“There must be an innovative interest on the part of an individual, because it is so complex, so many components in it.” (Development Manager, Defencecorp)

“The motivation of the individual must still be that there is somehow something coming back to [me] when I am acting this proactively … And … the reward system must still be linked to the payroll system that you are driving and finding new things and being proactive in terms of ideas and knowledge communication and distribution.” (Senior Project Manager, Minecorp)

“So, for better or worse, it is often the individual engineer who needs to ‘sniff out’ the right technologies and try to contact other networks and partners, and this is done from a need or hunger for new technologies and knowledge.” (Head of R&D, Defencecorp)

“Some individuals are just genuinely interested in technology. They take action, they read up on things, they follow and check on the latest developments. These individuals are very important for a technology‐oriented organization to move forward. I think that many of our developers and engineers are expected to and do take on a significant personal responsibility. I think motivation comes from just knowing that it is part of my job. That’s what I do, search for suppliers of technologies and find solutions to things … I think this needs to be encouraged more so that people really do it because, if I just sit and wait for something to fall into my lap, we will get nowhere. One has to be out there actively searching.” (Project Manager, Minecorp)

Evaluating technological feasibility

“Those who are less talented, they just identify something, [saying,] ‘Look, what a new idea.’ [Managers respond,] ‘Well, what should we do with it then?’ [And they say,] ‘I don’t know.’ These individuals are not particularly valuable and are, rather, causing interference by spewing out disinformation. They are not refining it to fit with our context.” (Technology Development Manager, Truckcorp)

“It often becomes an issue during development when you don’t have a sufficient level of knowledge [about the technology] but you’re trying to integrate it anyway, so you constantly encounter a problem that you don’t have a sufficient understanding of.” (Department Manager, Defencecorp)

“If you understand how this technology works, you understand how it can be integrated into the product, because you know it inside out. Then you know that we need to add or revise this part, and we need to remove this part to make the product work.” (Senior Development Engineer, Defencecorp)

“The challenge is really to sniff out these technologies, because it’s a jungle of information that can often be misleading. For the most part it’s a bit senseless, it’s not applicable. It comes down to capturing [what] … really can be something that is possible for us to apply now or in the near future … you must have some experience and analyze it critically when you hear something.” (Project Manager, Defencecorp)

Corroborating knowledge value

Demonstrating business value

“The key here is to be able to translate it into business for us and for the benefit of our customers. If you’re somewhat vague on that point, then it will not proceed further. It doesn’t matter how good you are on sales pitches, lobbying or drawing up PowerPoints. If you can’t explain it, then it stops.” (Technology Development Manager, Truckcorp)

“… these developments end up in technology portfolios that no one really picks up. Maybe I’m exaggerating, but it’s a feeling I have that to be able to productize that you would get … a bigger business benefit if you had a person with an understanding of the business model involved.” (Head of R&D, Defencecorp)

“Innovators who are churning out patents, they’re creative and … of course it could also be that they are a bit naïve because they don’t ask whether it’s commercially viable. They just think it’s interesting to find a theoretical or technical solution, but whether it’s commercially viable is a completely different question. And then you start to be critical, and maybe then you never get to the plate because it will probably never work. So, it’s a team you need, I think, and its various competencies that will work together in a balanced way for it to have really good effect on an overall business level.” (Project Manager, Defencecorp)

“Here is a huge gap. You can make a business case for a technology that has all the technical benefits but that’s impossible to sell! No, of course not. It’s not a product. So, such projects may in principle not start, and it’s really hard. Then I’ll be one of those guerrilla dudes, saying we take this on the line as well.” (Group Manager, Minecorp)

Ensuring legitimacy

“You have in your backpack a kind of trust equity; certain people’s words outweigh others when it comes to this phase. If you’ve been able to identify several solutions that have proven to be good when you’ve said they’re good and when you say it’s bad, it’s bad, then it’s obvious that it builds some credibility, and that makes the difference.” (Department Manager, Defencecorp)

“In such a large company, it’s more or less impossible to defend yourself if you start to get colleagues against you. If they think ‘You should watch out for him, he seems to have some strange ideas, it’s usually not so grounded, what he says,’ there’s a risk in that, and you don’t want to end up in that situation.” (Senior Researcher, Truckcorp)

“We have this guy who can influence a lot and make sure you talk about these things. I think it’s … partly that he has experience and has been in the field and has seen a lot. He’s knowledgeable, but also able to talk and is not put down by anyone and is almost a deity in his area.” (Manager R&D, Minecorp)

“It’s good to know who has the knowledge. … At this stage it’s important to exploit or use your network of contacts within the company to get help. ‘Do you see something wrong? I have this hypothesis, but is it right or wrong, and if so, why?’… when enough people say it looks good or it should work, then you have sufficient critical mass to be able to continue working on it. If you have an idea that you think and know is good but no one buys it, then it’s not so easy to get anything done.” (Department Manager, Defencecorp)

Championing knowledge integration

Lobbying for support

“I guess that’s what we’re struggling with all the time actually. This is the lobbying that I think … is probably our main challenge in the market department. To communicate what we do and get people in the organization to understand it and kind of see the opportunities with it.” (Project Manager, Minecorp)

“You go around and talk to some people, ‘Hey, I have something new that I’ve been investigating,’ and then it usually becomes a small snowball internally. As long as everyone thinks it’s a good idea, then it grows, and then it may be time to involve someone in a senior management position.” (Department Manager, Defencecorp)

“From a new employee’s perspective, it can be much more difficult. They have their coffee place, which is the only opportunity [they] have to talk to people. If you’re like me, a little longer in the game, then you have built up a decent network of contacts and know who knows what and which one you should go and talk to in order to get things done.” (Department Manager, Defencecorp)

Securing resources

“Often, it’s perceived as a niche product so there will never be anything. Should we add X number of engineering hours on such a small business when we could add X engineering hours on a much bigger deal? Then we shouldn’t [go for] this little project.” (Development Manager, Minecorp)

“You’ll get slapped on the wrist if you don’t keep to your budget. And then it’s how you are as a person, whether you’re able to navigate past these perilous rocks. And some handle it, and others are not that person.” (Senior Development Manager, Defencecorp)

“It can be difficult to gain support [for] the design. Let’s take composite materials as an example. It’s very difficult to recoup it. It’s an expensive material and difficult to find quick production processes for the volumes that we are working with in the automotive industry. So, there are lots of obstacles in the way, and it’s clear that in this case … you won’t get support … there may be those who think you’re pushing things that are too far ahead or that will never get [integrated] into the product.

There’s a sense that … [the] money and effort … could have been allocated to something else. So, it’s a balancing act.” (Head of Material Technology, Truckcorp)

“So, nothing happens. If you want money to be [spent on] tests, then you have to first describe the customer benefits of the solution and then have at least someone from marketing convinced that it is sellable. This means that those responsible for R&D, marketing, finance—everyone should participate in deciding what the money should be spent on. Then a majority needs to be in favor of developing it so we get it sold or … it will benefit us in some way … and here’s the rub: you need to actually come in and to have decided that this is a customer benefit beforehand.” (Department Manager, Defencecorp)

Knowledge absorption outcome

Exploitation

“If you find new things, which means that now we can actually produce the same thing as before but a little bit cheaper, then you get traction instantly and then you’ll see it integrated. On the other hand, if this is something that could change our product so that we reach a larger market or do something so we can get better paid, then there’s always a little heavier work required.” (Senior Researcher, Truckcorp)

“If you succeed in pushing through a large project in a new material technology—for example, composite materials—it doesn’t have to be a great innovation. But if you assimilate it in a sensible way so that you can count it home [make money on it] for a truck, then we try to encourage it by noting it in your salary increase, include it in the technical development as a good example, and we’ll find ways to show appreciation for the initiative [that you have taken].” (Head of Material Technology, Truckcorp)

“You know how chameleons are able to adapt the color of their skin to mimic the environment? I was working on something similar that would allow our vehicles to be undetected on IR scans. So I started searching for knowledge on this, and there were some technologies that could work. … Of course I was doing much of the experimenting since I thought it was stimulating, but once I had some results to present it was quite easy to motivate and get a team working on it. Sometimes it doesn’t have to be so difficult to integrate something new when the value is obvious. … And I think this has actually been a very important project for our organization, to show that we can be innovative up here.” (Senior Development Engineer, Defencecorp)

“It is satisfying to get the opportunity to [absorb an external technology]. … If I can just convince the next few colleagues and managers to believe in this, then I get an enormous boost in being able to do this, which I have envisaged for a long time. It’s like an Atlantic liner: if you go in the wrong direction, it will be very heavy to turn, but suddenly when it turns then and you have all this force with you. And maybe that’s the beauty of this process. You struggle to convince your colleagues and managers that this is the right way and they say, ‘We trust you’.” (Senior Researcher, Truckcorp)

Limbo

“It can be difficult for individuals pushing for new ideas but not getting through. I think few can keep pushing full throttle their whole career. Usually they wise up and start being more conservative about external ideas. Regrettably, I think, we lose something important then.” (Senior Manager, Defencecorp)

“During those years I almost burned out. I knew the importance of the technology and that this was the right way to go for the company, but my proposals for new projects kept getting shot down. It was like pushing through a brick wall.” (Research Manager, Truckcorp)

“Sometimes you can, as a technology worker, get your research money to explore an idea, and then you proceed to work until [there’s] a ‘gate.’ Then we evaluate and we weigh [it] against other bets and then maybe you get told, ‘We’ll put your research project on hold for a year.’ That’s a disincentive and a frustration for individuals. I’m sometimes a bit afraid that they’ll leave and jump to some other company where they can find an outlet for their creativity.” (Head of R&D, Defencecorp)

“Management had basically terminated the project and said that they couldn’t continue working. But these guys were sitting and working anyway. There was a strong person in the design department who believed in the potential of this technology. Many times, it’s like that. I guess there was something similar with the Losec development that they developed it a bit hidden. I don’t know if this would work today with the large multinational corporations that demand transparency and governance of every hour you work.” (Senior Manager, Defencecorp)

Termination

“At the core of it, I think you form your own opinion. ‘Is this something I believe in or not?’ And if you believe in it, then you choose to share it, and if you do not believe in it, then you leave it alone.” (Senior Project Manager, Minecorp)

“There can be strong resistance to bringing in new technologies. I think it is especially strong when it threatens our established areas of competence. One example is electric propulsion, which has been shot down in many internal meetings … it won’t work, they say. But overall I think many fear that their competencies will be obsolete.” (Senior Researcher, Truckcorp)

“There’s a danger with closing down things, because you can wear down this person who engages in so many ideas. He feels it’s not worth it anymore.” (Senior Research Manager, Defencecorp)

“I’ve probably driven [an idea] all the way … and when you get a bit further you realize, ‘No, this is not going where I intended it to be going,’ and then it’s time to stop.” (Group Manager, Minecorp)

Diagrams and table © 2018 The Authors, Journal of Product Innovation Management published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc; from https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12482

Comment:

The findings of this paper rang very true with me from my many years working as an R&D manager in industry. The most effect bringers of new external ideas (and ideas in general, regardless of source) into the organisation were the ones that had a passion for new ideas and technology, often spending much personal time in exploring this. They knew the company system and how to get round it and had a large internal network of people with whom they could both officially and unofficially collaborate on new ideas and technology. They were not only tech-savvy but business-savvy having an understanding of their division’s and the company’s business goals and strategy as well being technically astute.

In the company that I worked for the idea of “bootlegging” or “skunk-works”, as we called it, was quite normal and accepted.

“If you are not working on at least two projects that I know nothing about, you’re not doing your job…” I once heard an MD say to our technical director.

Skunk works were even semi-formalised to a degree with small money pots, semi-annual “seed-corn” grants, made available to ideators for pursuit of such ideas. Individuals who wanted to (the innovators) were allowed considerable autonomy and freedom to do this under the “15% rule”.

Those individuals who were good at finding new ideas and technologies, working on them to establish their technical feasibility and potential value, and who could effectively sell those ideas internally to turn them into fully fledged projects and, ultimately, new products were the ones who made it up the technical ladder as technical specialists and division or corporate scientists.

At that level, these individuals became (and were expected to become) mentors for more junior individuals who could use them to test out the technical and commercial feasibility and fit of new ideas and technologies that they came across.

Learning points – encouraging AC

As an R&D manager, the value of this paper lies in recognising the above important elements that lead to an individual being successful at bringing external ideas and technologies into a company and facilitating those within your own company through, for example:

- CPD training on:

- The company technology and business strategies

- Networking

- Online library service usage

- Patent landscaping

- Business case preparation, etc.

- Mentoring

- Allowing free time to gather external knowledge

- Recognition for new knowledge acquisition

- Proactive processes for updating the organisation on external technology and market trends

- Making such knowledge acquisition part of the role and promotion path of technical specialists

Overall, a paper worth your time reading.

The paper: How Individuals Engage in the Absorption of New External Knowledge : A Process Model of Absorptive Capacity David Sjödin , Johan Frishammar, and Sara Thorgren J PROD INNOV MANAG 2019;36(3):356–380 © 2018

Journal of Product Innovation Management published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on behalf of Product Development & Management Association DOI: 10.1111/jpim.12482

Reviewed by:

Phillip A. Kennedy, PhD FIKE

Visiting Professor, Queen Mary University of London,

School of Engineering and Materials Science