“It’s fantastic being here and the conference itself was wonderful,” says Jeremy Klein, Chairman of RADMA, about The Next Generation R&D Management in China Conference, which was held in Wuhan from 15-17 September 2024. “The hospitality is fantastic too – I’m having feast after feast! The level of development in China and the sheer scale takes one’s breath away. I just arrived on the bullet train at 300 km/h!”

Jeremy was one of the keynote speakers on the first day of the conference. In his session, Jeremy talked about how the field had evolved over 50 years, drawing out the shifting fashions in strategy thinking. He argued that whereas when the R&D Management Journal was launched in 1970, R&D management was a topic of secondary importance, now the world’s top companies are organised with innovation as a core mission so they are designed for innovation. This, he said, meant that R&D Management was now more important than it had ever been before.

In this post for R&D Today, Jeremy gives his thoughts on the rest of the conference and his stay in China.

The conference was organised to a very high standard. There were around 100 attending, with about 30 PhD students from HUST, the host institution. Xiaolan Fu had six of her Oxford PhD students there too. There were also academics from around China including Hong Kong, Beijing and Xian.

The event started with a Doctoral Colloquium as per the main R&D Management Conference but lasting only half a day. That said, it was clearly valuable for the students to be challenged by a panel of experts from outside Wuhan.

The event proper lasted over one and a half days, with ten keynotes. While most were based on datasets from China, the topics were all of wide interest and applicability. The Meet the Editors session included R&D Management, Technovation and Organizational Science. What stood out for me was the quality of questions and the high quality of discussions generally.

Day 1 Keynote sessions

Max von Zedtwitz (Copenhagen Business School) gave a fascinating account of his analysis of the 646 Nobel Prizes awarded since their inception. Drawn largely from a forthcoming paper, there were several surprises. Nobel Prize winners are awarded their prizes later in life than previously, though the invention or discovery for which the prizes had been awarded was not correspondingly later. As the gap is now around 25 years, China’s current poor showing is a consequence not of its capabilities today but those of 25 years ago. There are marked differences between countries, states in the US and institutions. Some institutions are good at providing the basis for prize winning research to be done, but less so at holding on to their winners.

Xiaolan Fu (Oxford University) gave a wide-ranging talk on the uses of AI in social science research. She questioned the motivation behind some humanoid robots. Her own research as used AI to produce validated models to value IP in tech transfer scenarios.

Zhi Yang (Dean of the HUST Management School) gave a thoughtful presentation concerning the impact of novelty on tech transfer out of universities. He argued that there is an inverted U relationship in which too much novelty impedes tech transfer as the investor audience is too unfamiliar with the transferable IP to be able to value it.

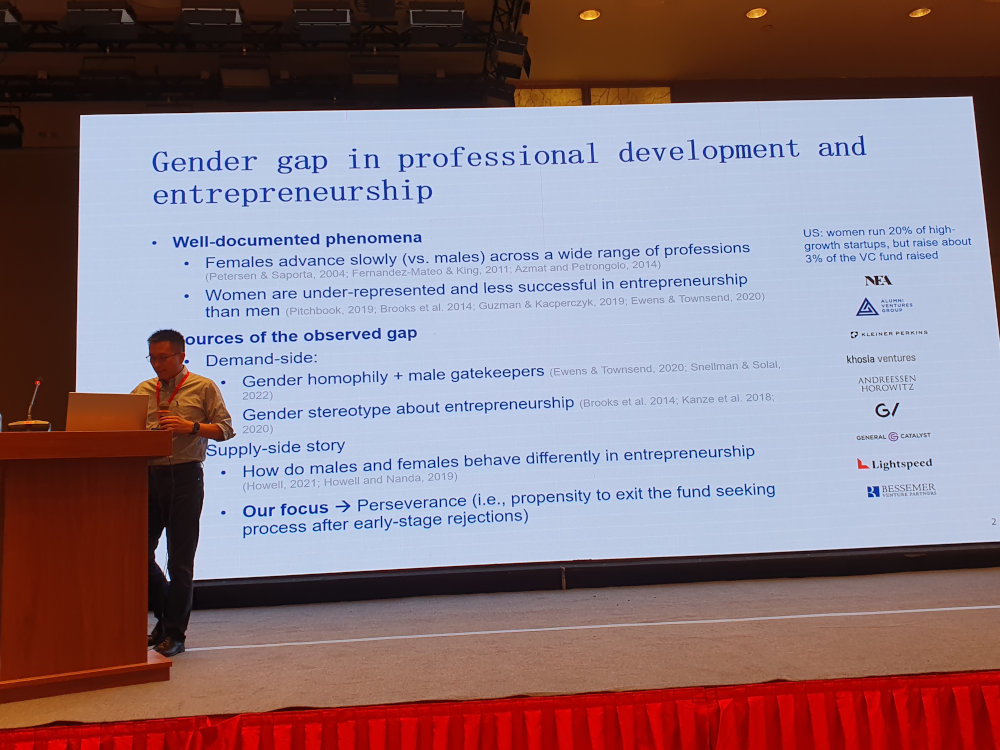

Yanbo Wang (University of Hong Kong) has been exploring gender effects in how applicants respond to rejection from funding competitions. The striking result was that women tend to respond to the aggregate score and comments whereas men tend to pay more attention to the most positive feedback. As a result, women are far less likely to re-apply following rejection. This was a quantitative study using data from Beijing.

In the afternoon of the first day there were both parallel tracks and a company visit for the non-Chinese participants.

The day ended with a cruise on the Yangtze River. Being the Chinese mid-autumn festival there were festivities and entertainments such as fire eating.

Day 2 Keynote sessions

Xielin Liu (University of Chinese Academy of Sciences) looked at the comparative impacts of curiosity-driven research and mission-driven research. He used data from the 735863 projects funded by the Natural Sciences Foundation (NSF) of China together with a questionnaire survey. He found evidence to support the idea that the NSF’s curiosity-driven programmes were more effective in building China’s frontier science and technology capabilities.

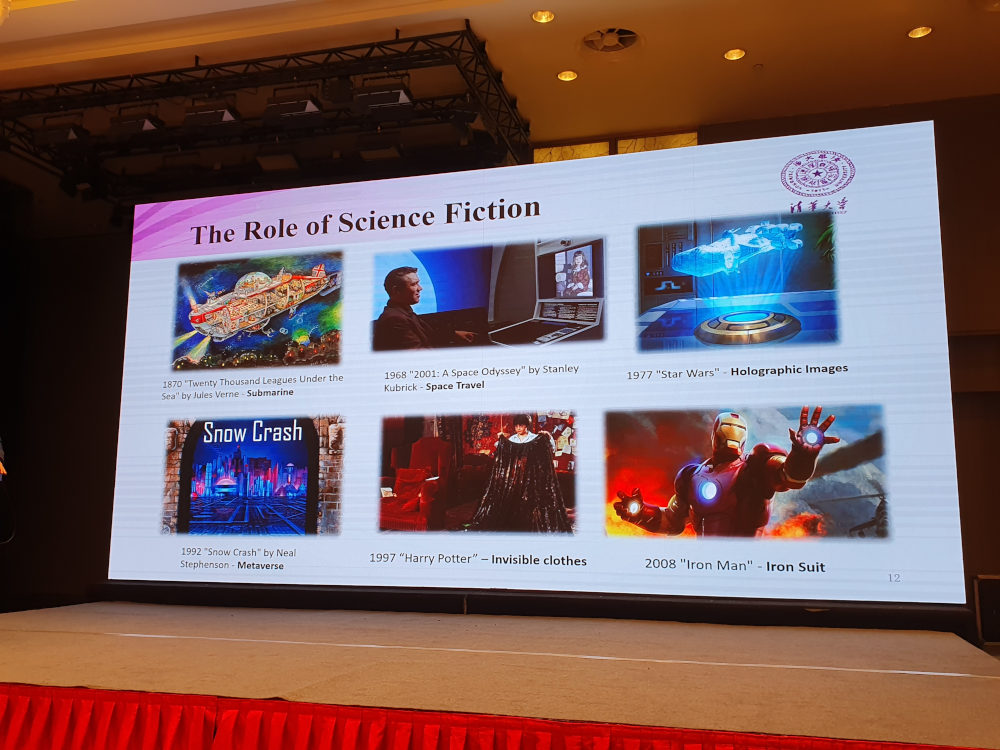

Jing Chen (Tsinghua University) gave a range of fascinating examples of the use of AI in innovation. It’s hard to pick out a winning example but several audience questions picked up on what I thought was an interesting part of his talk, namely the use of AI to analyse the innovations included in science fiction stories. He argued that whereas we have many retrospective sources of data, science fiction embodies social imagination regarding the potential use cases of technologies.

Jiang Yu (Institutes of Science and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences) discussed his work on open source hardware (OSH). He noted that much attention has been given to open source software but far less to hardware. And yet, large data centre customers in China such as Baidu, Tencent, Alibaba have collaborated using open innovation thinking to shift the power away from incumbent hardware suppliers. He proposed a model of how shifting horizontal and vertical collaborations can explain the evolution of OSH.

Yuan Zhou (Tsinghua University) looked at the career backgrounds of Chinese officials involved in Outward Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI). The study used AI to analyze the records of thousands of officials and suggested that officials with backgrounds in technology fields tend to be more willing to take risks.

Weiwen Li (Sun Yat-sen University) looked at the free-rider problem in patent inventorship. Using carefully curated data sets he found evidence that when CEOs force their names onto patents as co-inventors despite having no actual involvement, then there is a demotivating and ultimately innovation-reducing effect throughout the company.