The Silicon Valley of India has consistently ranked in the top 25 start-up ecosystems internationally and the country boasts 100 unicorns (businesses with a value of over $1billion). Additionally, nearly a quarter of the world’s engineers originate from India. It is against this background that the country is exploring the potential of ‘technological sovereignty’ to decrease its reliance on imported products.

RADMA scholar Simon Frederic Dietlmeier, a PhD Candidate at the University of Cambridge, is investigating the potential of India to become more self-reliant in technology and to have self-determination in critical areas such as AI. In this article he uses the case-study of the Short Form Video market to explore the concept.

Simon is a member of Konrad Adenauer Foundation’s Doctoral College “Social Market Economy”. His research features novel trends in ecosystems, platforms, and the digitalization of industry at the intersection of strategic management and public policy. He has been awarded funding in the 2022 Doctoral Studies Programme for 2022/23 and 2023/24.

History of the Indian entrepreneurial economy

India is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, and numerous research works on its national and regional entrepreneurial ecosystems have already been conducted.

Historically, post-colonial India established itself as a protectionist country, aiming towards strategic autarky (self-sufficiency) in the aftermath of British colonial rule (Racine, 2008). The polity remained a largely closed economy, but in 1991, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi announced the liberalisation of India (Shastri, 1997), a step that was later followed by India joining the World Trade Organisation (Chishti, 2001).

This decision opened the Indian market to foreign multinational corporations (MNCs) and the development laid a foundation for the creation of the national and regional entrepreneurial ecosystems in India.

Driven by demand for outsourcing

The evolution of the technological ecosystem was driven by a desire for cheaper outsourcing services by multi-national corporations. Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), Wipro and Infosys were domestic firms that leveraged this opportunity by utilizing the country’s English-speaking population. They invested in technology to ensure that India was globally known for a cost-effective technology service sector (Bala Subrahmanya, 2017b). Foreign companies such as IBM and Intel entered the market, and simultaneously, India has grown a technically capable talent pool with a culture of educating engineers.

Nowadays, the Indian technology sector is worth $200 billion, employs over 5 million people (Ghosh, 2022) and a large share of one fourth of the world’s engineering graduates have their origins in India (Falkenheim, 2018, p. 115).

Bangalore is the location of choice

Most of Indian high-tech companies established themselves in Bangalore, a hub for public sector industries at the time. For example, the national aerospace, telecommunications, heavy engineering, defence and space manufacturers are all based in the city (Yousaf, 2016). This incentivized the government to invest massively into the Bangalore ecosystem, and many important firms established a base there as preferred location of choice during the 90’s IT revolution. MNCs chose to headquarter themselves in Bangalore to leverage the city’s highly skilled talent pool.

The increase of foreign companies’ presence further reinforced Bangalore’s standing as the principal technology hub of India. In the 2000s, the Karnataka state government began to create targeted policies to attract start-ups to Bangalore as their hub (Bala Subrahmanya, 2017a,b).

Creation of the ‘Silicon Valley of India’

The IT revolution further contributed to the growth of other sectors such as robotics, telecommunications, and advanced manufacturing. This development led to an improvement of Bangalore’s infrastructure, which manifested its colloquial name as the “Silicon Valley of India” (Saraogi, 2019).

Since then, the city has consistently been counted amongst the top 25 start-up ecosystems worldwide (Majumdar, 2021; David, 2022). India as a whole is meanwhile ranked one of the top 5 start-up ecosystems alongside the United States, China, the United Kingdom, and Israel (Sitharaman, 2022).

As of 2022, India also has over 100 unicorns (Goyal, 2022). They generally receive a high amount of funding, with an average Indian company raising double the amount of funding as compared to Israel that comes in second place (Kashyap, 2022). The by far largest share of unicorns is based in the tier 1 city Bangalore with 43% of unicorns, followed by Delhi NCR with 33% (Dayalani, 2021).

Technological sovereignty in India

Research on technological sovereignty in India is limited though, however a few publications in the grey literature thematize the concept.

A report on Technological Sovereignty and India asserted that India should enhance self-reliance by relying on its domestic market and decreasing dependence on foreign products, whilst investing and developing homegrown alternatives (Mathias et al., 2021).

The report also mentions that foreign applications on Indian smartphones could be used to “create inimical situations for India” (p. 27). Indian entrepreneurs would therefore have the chance to develop alternative apps in response to the ban of foreign apps by the central government.

The Indian government has also created nationalistic concepts known as Atmanirbhar Bharat, which translates to “Self-Reliant India”, in addition to initiatives such as Make in India. This adds to India’s aim to act strategically and autonomously in critical areas such as artificial intelligence (AI) and manufacturing (Madhavan, 2021).

It was suggested before that technological sovereignty might be achievable in India by localisation and development of homegrown products (Bhatacharya, 2020).

Case example: The Indian short form video market

The SFV market within India provides a promising case for the link of technological sovereignty and entrepreneurial ecosystems. SFVs are digital B2C content that lasts between 15 seconds and 2 minutes, and applications that provide access to the content have become rising stars in app stores.

The SFV market in India began to flourish with the entry of the Chinese technology firm Musical.ly in 2017, which resembled a large user base and championed the SFV trend in India (Sheth et al., 2021).

In 2018, another Chinese firm, ByteDance, acquired Musical.ly and merged it into its TikTok™ product. This SFV app experienced an enormous surge in users within the country and became the application’s largest market, with more than 200 million users in 2020 (Sheth et al., 2021).

Ban on apps hits rise of Chinese TikTok

The rise of TikTok™ triggered the creation of a large creator economy and ByteDance counted more than 2000 employees within its Indian operations (Singh, 2021).

However, in 2020, geopolitical tensions between China and India increased after a deadly military clash in the Galwan Valley, which resulted in rising diplomatic and geopolitical tensions between the two nations (Anbarasan, 2021).

The Indian government retaliated economically with a ban of 59 Chinese apps, and the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology stated that the sovereignty of data has nowadays national security implications:

“The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology has received many complaints from various sources including several reports about misuse of some mobile apps available on Android and iOS platforms for stealing and surreptitiously transmitting users’ data in an unauthorized manner to servers which have locations outside India. The compilation of these data, its mining and profiling by elements hostile to national security and defence of India, which ultimately impinges upon the sovereignty and integrity of India, is a matter of very deep and immediate concern which requires emergency measures”. PIB Delhi (2020)

Gap in the SFV market fuels demand for sovereign apps

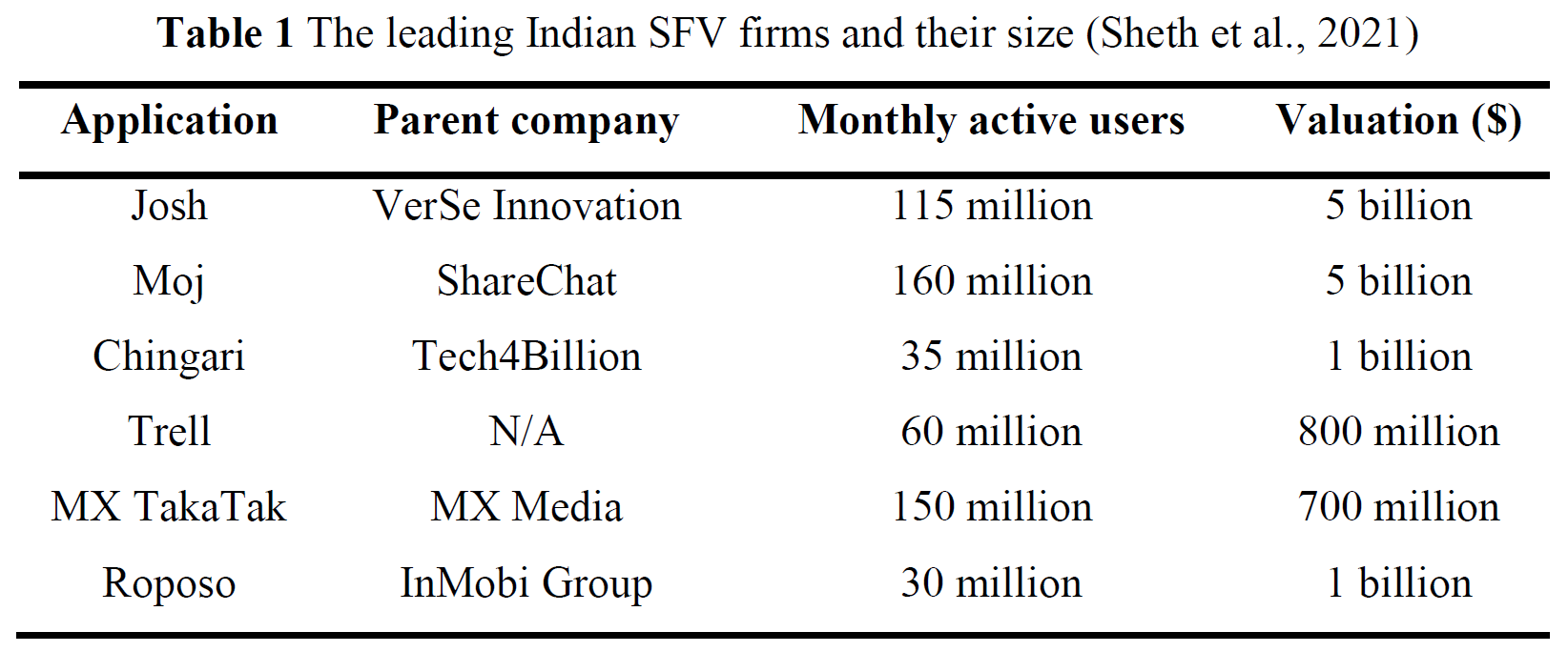

Of the 59 applications banned, the most significant one was TikTok™ due to its large user base in India, which left a substantial gap in the country’s SFV market – especially in rural regions and tier 2/3 cities. The Galwan Valley incident and subsequent ban of Chinese applications resulted thus in a significant market opportunity for Indian content creators and end users, which motivated many Indian start-ups to enter the market and advertise themselves as homegrown “sovereign” apps. Table 1 illustrates the main applications that succeeded in establishing themselves within the Indian SFV market.

Boom in domestic creator economy

The overview shows that six companies have begun to dominate the Indian SFV market, three of them resembling over 100 million daily active users. The overall market is nowadays valued at $11.6 Billion and is still growing, with presently over 350 million active users in the country and a predicted 650 million users by 2026 at a market valuation of $18 billion; in comparison, TikTok™’s overall global value is estimated at $50 billion (Sheth et al., 2021).

The two applications that dominate the Indian SFV market nowadays are Josh™ and Moj™. The parent companies for these apps are both valuated at $5 billion in 2022 (Sarkar, 2022a,b). Competitors such as Chingari™, MX TakaTak™, Glance Roposo™, and Trell™ have nevertheless seen significant growth, as well. This has fuelled a large creator economy, and the fast growth has allowed these companies to expand internationally (Salman, 2022).

Notably, all the homegrown SFV companies are based in Bangalore for their core operations. This case thus had the potential to investigate the impact of entrepreneurial ecosystems as an enabler of technological sovereignty.

In this context, technological sovereignty would describe the prevalence and favouring of homegrown (Indian) apps instead of a foreign app to increase the “national technological competitiveness” (Edler et al., 2020).

References

Anbarasan, E (2021). China-India clashes: No change a year after Ladakh stand-off. BBC News, News Item, June 1. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-57234024 (Accessed 19-05-2022).

Bala Subrahmanya, MH (2017a). Comparing the entrepreneurial ecosystems for technology startups in Bangalore and Hyderabad, India. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(7), 47–62.

Bala Subrahmanya, MH (2017b). How did Bangalore emerge as a global hub of tech start-ups in India? Entrepreneurial ecosystem, evolution, structure and role. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 22(1), 1–22.

Bhatacharya, J (2020). Technological sovereignty and how India lacks it. StratNews Global, News Item, June 8. Available at: https://stratnewsglobal.com/trade-tech/technological-sovereignty-and-how-india-lacks-it/ (Accessed 04-07-2022).

Chishti, S (2001). India and the WTO. Economic and Political Weekly, 36(14), 1246–1248.

David, E (2022). Global startup ecosystem 2022: Ranking 1,000 cities and 100 countries. Crunchbase, News Item, June 16. Available at: https://about.crunchbase.com/blog/trends-global-startup-ecosystem-2022/ (Accessed 13-07-2022).

Dayalani, V (2021). Indian startups turning unicorns 2X faster than a decade ago. Inc42, News Item, April 10. Available at: https://inc42.com/datalab/indian-startups-turning-unicorns-2x-faster-than-a-decade-ago/%7D (Accessed 10-06-2022).

Edler, J, K Blind, R Frietsch, S Kimpeler, H Kroll et al. (2020). Technology Sovereignty: From Demand to Concept. Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (ISI), Germany.

Falkenheim, J (2018). 2018 Science and Engineering Indicators. National Science Foundation, USA.

Ghosh, D (2022). Technology Sector in India 2022: Resilience to Resurgence. NASSCOM Insights, India.

Goyal, P (2022). States’ Startup Ranking 2021 on Support to Startup Ecosystems. Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), Ministry of Commerce and Industry, India.

Kashyap, H (2022). India’s unicorn boom: Where does India stand in the global arena?. Inc42, News Item, May 18. Available at: https://inc42.com/features/indias-unicorn-boom-where-india-stand-global-arena/ (Accessed 01-07-2022).

Madhavan, N (2021). What exactly is Atmanirbhar Bharat?. The Hindu Business Line, News Item, April 15. Available at: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/what-exactly-is-atmanirbhar-bharat/article34328520.ece (Accessed 04-07-2022).

Majumdar, R (2021). Bengaluru ranks 23rd in global startup ecosystem list. Inc42, News Item, September 23. Available at: https://inc42.com/buzz/bengaluru-ranks-23rd-in-global-startup-ecosystem-list- delhi-on-36th/ (Accessed 10-07-2022).

Mathias, L, T Chakrabarty, A Kirloskar, K Brothers, T Bagrodia et al. (2021). Technological Sovereignty and India. Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, India.

PIB Delhi (2020). Government blocks 118 mobile apps which are prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of state and public order. Ministry of Electronics & IT, Press Release, September 2. Available at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1650669 (Accessed 14-06-2022).

Racine, JL (2008). Post-post-colonial India: From regional power to global player. Politique Étrangère, 5, 65–78.

Salman, SH (2022). VerSe Innovation goes global, expands operations to the Middle East. Financial Express, News Item, June 21. Available at: https://www.financialexpress.com/industry/verse-innovation-goes-global-expands-operations-to-the-middle-east/2567141/ (Accessed 06-06-2022).

Saraogi, V (2019). How the tech city of Bangalore became the Silicon Valley of. Elite Business, News Item, April 17. Available at: http://elitebusinessmagazine.co.uk/global/item/how-the-tech-city-of-bangalore-became-the-silicon-valley-of-india (Accessed 22-10-2022).

Sarkar, J (2022a). ShareChat closes $520 million round at $5 billion valuation. The Times of India, News Item, June 16. Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com /business/startups/companies/sharechat-closes-520-million-round-at-5-billion-valuation/articleshow/92259394.cms?from=mdr (Accessed 14-07-2022).

Sarkar, J (2022b). VerSe raises $805 million at $5 billion valuation. The Times of India, News Item, April 6. Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/verse-raises-805-million-at-5-billion-valuation/articleshow/90674791.cms (Accessed 14-07-2022).

Shastri, V (1997). The politics of economic liberalization in India. Contemporary South Asia, 6(1), 27–56.

Sheth, A, S Unnikrishnan, S Krishnan and M Bhasin (2021). Online Videos in India – The Long and Short of It. Bain & Company, India.

Singh, M (2021). ByteDance is cutting jobs in India amid prolonged TikTok ban. Tech Crunch, News Item, January 27. Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2021/01/26/bytedance-to-cut-jobs-in-india-amid-tiktok-ban/ (Accessed 04-07-2022).

Sitharaman, N (2022). Key highlights of the economic survey 2021-22. Indian Ministry of Finance, Press Release, January 31. Available at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1793829 (Accessed 07-07-2022).

Yousaf, S (2016). How Bengaluru became India’s startup capital. CNTraveller, News Item,

March 7. Available at: https://www.cntraveller.in/story/how-bengaluru-became-indias-startup-capital/ (Accessed 11-06-2022).

Author Biographies

Simon Frederic Dietlmeier, MSc MPhil

Simon Frederic Dietlmeier is a PhD Candidate at the University of Cambridge, and a member of Konrad Adenauer Foundation’s Doctoral College “Social Market Economy”. His research features novel trends in ecosystems, platforms, and the digitalization of industry at the intersection of strategic management and public policy. He received multiple renowned scholarships and awards. Simon has experience in industry with Siemens, Airbus and BMW; as well as in policy with the Munich Security Conference (MSC), the Federal Foreign Office, the Federal Ministry of Finance, and the Bavarian Parliament. As its long-time Chairman, he relaunched the TUM Speakers Series and was selected in DLD Media’s “50 for Future” class of 2020. He is a Global Shaper of the World Economic Forum’s Community and was Co-Chair of the Advisory Board of TUM Speakers Series. Simon co-founded the G7-75 Years Marshall Plan Young Transatlantic Leaders Initiative.

Nehaal Vipin Pillai, MEng MPhil

Nehaal Vipin Pillai is a strategy consultant at Mansfield Advisors in London and a collaborator within the Institute for Manufacturing in Cambridge (IfM). He holds an MEng in Aeronautical Engineering from Imperial College London and an MPhil in Industrial Systems, Manufacture and Management from the University of Cambridge. His professional work comprises consulting projects in the healthcare, aerospace and telecoms, media & technology (TMT) sectors. Nehaal has consulted leading Silicon Valley technology firms, Deutsche Bank, and the British National Health Service (NHS) on operational and strategy related projects. He has a deep interest in geopolitics, and has written and published several student newspaper articles for Imperial College’s “Felix” on India, China, and the United States covering topics such as trade, economics, and business.

Dr Florian Urmetzer

Dr Florian Urmetzer is an Associate Teaching Professor and an Executive Course Director at the University of Cambridge. He is conducting research in the area of business ecosystems and teaches industrial economics, strategy, and governance. Florian’s work was published in journals such as the Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Information Systems, and Journal of Service Research. He holds a doctoral degree in Computer Science from Reading University, and he was a visitor to the Barcelona Supercomputing Center. His output has been adopted by companies like IBM, ATOS, ABN-AMRO, CEMEX, Pearson Education, Leonardo Rescue Helicopters, and the NHS. Prior to joining the University of Cambridge, Florian worked in consulting for Accenture in Zürich, and as a Senior Researcher in the SAP labs, for Volkswagen AG, Gartner Inc., and IBM.