How do you balance the generation of short-term profit, gained from the exploitation of existing knowledge and success patterns, with long-term success achieved from building up new knowledge, new solutions and new structures? Patrick Olivan, with the support of Prof. Joachim Warschat, discusses the design of an ambidextrous organisation that can sustain daily business while pursuing radical innovation.

Introduction

Innovation processes, supplemented by methods and evaluation criteria, are now part of the standard repertoire of many companies. However, the identification, evaluation and implementation of so-called radical innovations is and remains a challenge, as these are often perceived as sand in the gears of efficiency-driven day-to-day business. One approach to solving this problem is ambidextrous organisational structures, which allow specialisation and coexistence of both innovation modes.

What is Ambidexterity?

Ambidexterity means to be equally skilfully trained with both hands and the ability to perform independent activities with each hand. In business administration, the term ambidexterity was introduced about 20 years ago in the context of the management of innovations and organizations (Tushman & O’Reilly 1996). Ambidexterity is understood as the ability to run an efficient day-to-day business (exploitation) while pursuing radical innovations (exploration) in order to ensure the short and long-term success of a company (Tushman & O’Reilly 1996:24).

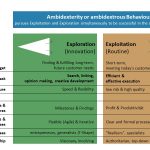

In ambidexterity, an important basic principle from organisational design is used. If the organisational design is optimised either for exploitation or exploration, specialisation makes it possible to achieve excellence in the respective task (Güttel & Konlechner 2014:354). As a result, all design factors must be consistent in themselves and must be aligned with one another so that the correct behaviour of all participants with regard to objectives, task and culture can be achieved (see Figure below).

Exploitation‘s objective is to meet the short-term wishes of customers while saving costs and developing the solutions offered incrementally in small steps. In order to pursue this objective as excellently as possible, the execution of existing products and business transactions is to be optimised for efficiency and effectiveness. Organisational structures have to be formalised in order to achieve increasingly higher margins and productivity as stable and error-free as possible. In addition, the specialization of employees allows clear responsibilities and an authoritarian management style to handle routine tasks more and more efficiently. The organisational designs promotes a behaviour of the employees that represents a culture of discipline that does not make mistakes, a so-called process culture (Tushman & Euchner 2015:18).

The objective of Exploration is to address long-term and currently not yet explicitly known customer needs in order to develop new products and businesses and enable new growth. To be excellent in this task requires agile, non-routine, i.e. iterative processes to develop creative and radical new solutions. The organisational design includes a visionary management style that leaves open the paths to be followed by generalist employees in order to reconnect ideas and knowledge and achieve a long-term goal. The culture being established in the field of exploration is one of risk and experimentation. The organisational design promotes an employee behaviour in which one is prepared to make mistakes in order to learn quickly and, if necessary, to take other paths.

The explanations on exploitation and exploration show that the respective coherent organisational designs are not necessarily in harmony. Depending on the task at hand, completely contradictory design conditions must be created within the company in order to achieve the desired behaviour and working methods of the partners and employees involved. This contradiction is at the centre of the challenge of an ambidextrous organisational structure.

Basic Implementation Strategies

To implement both tasks in one organization, a separation is required which enables opposing organisational design conditions. There are three basic design options possible: sequential, contextual, and structural separation (see O’Reilly & Tushman 2004)).

Sequential separation means for example do design an entire organization first in exploration and then to transform it into an exploitation design. This sequential change typically occurs in the development phase of a young small business to more mature medium-sized or large companies. However, with a certain size of a company, this design change is no longer effective and very difficult to implement. Contextual separation benefits of same employees, which work in a primary organization and is aligned to exploitation day-to-day business, but when they work in a project-based secondary organization it is designed as exploration. Employees need to change their behaviour and working culture depending the context, which not many are able to. Structural separation uses different employees in separate organizational units. A major advantage is that specialisation and the associated work culture is easy to implement. One of the disadvantages compared to the contextual separation is that a transfer of knowledge between the separate units has additionally to be organized.

Depending on the options available in a company, capabilities of employees, the maturity of an innovation project, even more precise design recommendations can be made. For that a method has been developed to implement ambidexterity for radical technology development (see Olivan 2019).

Conclusion

A company with the capability for ambidexterity integrates the conflicting design conditions and thus creates the basis for long-term success. In the area of exploitation, the focus is on the use of existing knowledge and success patterns to generate short-term profit. In the field of exploration, on the other hand, the focus is on building up new knowledge, new solutions and new structures in order to secure long-term success and to control and implement disruptions in one’s own business activities through radical innovation.

According to the ambidexterity principle, it is therefore necessary to pursue both tasks to the same extent or with the same intensity in the sense of a balance. Ideally, a company carries out a cyclical process in which it constantly learns new things, makes adjustments in the process and transfers this profitably into daily business.

As an introduction to this field, we would like to recommend following articles:

- O’Reilly, C.A. & Tushman, M.L. (2004): The ambidextrous organization, Harvard Business Review 82(4), 74–83.

- Tushman, M.L. & Euchner, J. (2015): The Challenges of Ambidextrous Leadership, Research-Technology Management 58(3), 16–20.

- Tushman, M.L. & O’Reilly, C.A. (1996): The ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change, California management review 38(4), 8–30.

- Güttel, W.H. & Konlechner, S.W. (2014): Ambidextrie als Ansatz zur Balancierung von Effizienz und Innovativität in Organisationen, in W. Burr (ed.), Innovation: Theorien, Konzepte und Methoden der Innovationsforschung, pp. 345–372, Kohlhammer Verlag. (In german language)

- Olivan, P. (2019): Methode zur organisatorischen Gestaltung radikaler Technologieentwicklungen unter Berücksichtigung der Ambidextrie. (in german language)

Post written by Patrick Olivan with Prof. Joachim Warschat

Patrick is Innovation Manager at LAPP Holding AG, Stuttgart, Germany. He completed his PhD at the Institute of Human Factors and Technology Management IAT at the University of Stuttgart in Germany. In his PhD he developed a method to implement ambidexterity for radical technology development according to their maturity. Visit his LinkedIn profile here.

Prof. Joachim Warschat is director at the Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering in Stuttgart, Germany and Professor at the University of Hagen for Technology – and Innovation Management. Visit his LinkedIn profile here.